What’s the value of Chickens in reducing food waste?

Backyard chickens are adding the role of “food recycler” to the list of benefits they bring to their communities, by reducing the volume of unwanted food going into landfills.

Austin, Texas recognized their value when they pioneered a zero-waste program where they pay citizens to keep backyard chickens. The goal of the program is to reduce the food entering landfills by redirecting it to backyard chickens.

Unwanted food in landfills creates methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Unwanted food fed to backyard chickens creates fresh eggs, a potent source of protein.

But is this valuable? Or true? We need to know more about how much unwanted food is eaten by a typical backyard chicken before boasting about their value as food recyclers. I studied this question as the thesis for my recent Doctor of Public Administration degree from West Chester University in West Chester, Pennsylvania.

Waste not, want not

Food is not meant to be wasted. Yet, approximately one-third of the food produced for human consumption goes uneaten and approximately 15% of municipal solid waste (MSW) is food.

Each person in the U.S. throws away approximately 300 pounds of food each year.

Food is not meant to increase MSW disposal costs, which are increasing annually. Landfill costs rose 16.9% from 2010 to 2017 in the U.S. when overall inflation was only 12%. Unwanted food increases the volume of MSW, straining landfill capacity near densely populated areas. We taxpayers bear the burden of these costs.

Food is not meant to damage the environment. In addition to the costs of placing food in landfills, environmental impact arises when food waste decomposes anaerobically in a landfill and produces methane gas—which contributes to climate change.

A methodology of scraps

We need to know how much food can typically be consumed by a backyard chicken to appreciate their value in reducing wasted food entering landfills. We can then estimate the economic value of backyard chickens as an alternative to landfills.

My study recruited eight households in or near Philadelphia, Penn. that owned backyard chickens from September 2018 to January 2019. Their food waste was weighed for one week during each month and the values were extrapolated to estimate a full year. The cost saving from not landfilling the household food scraps was compared to the alternative of placing the food waste in a landfill.

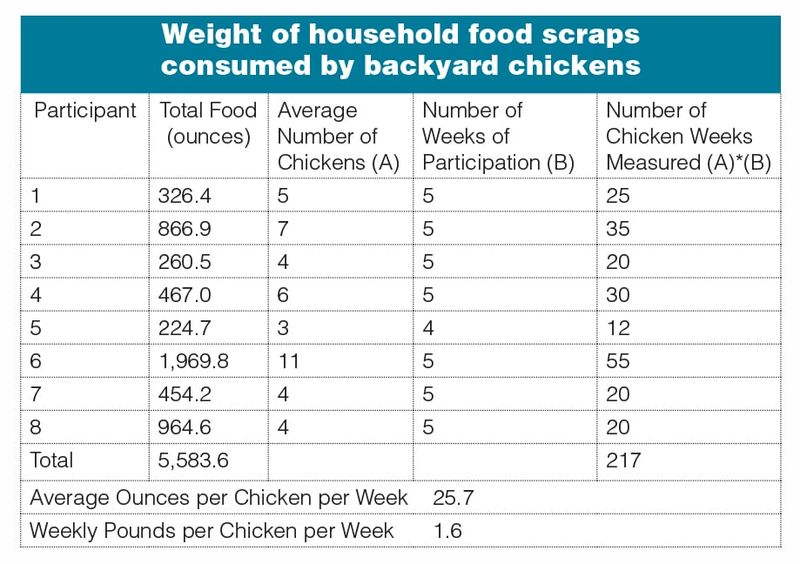

Participants weighed the household food scraps they fed to their backyard chickens. The total weight of the food scraps was summed for the five weeks studied. The average number of backyard chickens was determined for each participant and multiplied by the number of weeks the participant was in the study. The result is the average weight of household food scraps that a backyard chicken can be expected to consume in a week. The average expected weekly consumption was then multiplied by 52 to provide an estimate of the average expected annual consumption.

Surprising poundage

In most measurement weeks, 44 backyard chickens participated in the research study. The total weight of the food consumed during the five weeks studied was 5,583.6 ounces or approximately 350 pounds.

Each chicken ate a weekly average of 1.6 pounds of household food scraps.

A backyard chicken consumes approximately 1.6 pounds of household food scraps per week, or approximately 83.2 pounds of household food scraps per year. A flock of four backyard chickens would be expected to consume approximately 332.8 pounds of household food scraps per year, about as much as the average food wasted by each person in the U.S. each year.

The average expected annual consumption was compared to an estimate of municipal costs to dispose of MSW to measure the value of backyard chickens in reducing MSW costs.

Austin, Texas was the only municipality with a public program using backyard chickens to reduce MSW management costs in May, 2019, so their costs were used as estimates in the analysis.

Their cost to dispose of a ton of organic waste material is approximately $163. Therefore, a small flock of four backyard chickens saves approximately $27.04 per year in disposal costs. So now we know the economic value of backyard chickens and can measure their financial contribution to reducing MSW costs.

The four ways this was evaluated

Four techniques were used for the financial analysis.

The payback period, the length of time necessary to recover the initial costs of a program.

The net present value (NPV), the sum of all future cash flows discounted to their current value.

The internal rate of return (IRR), often considered the rate of return earned by a project.

The profitability index (PI), a measure of the return compared to the cost.

The financial analysis methods require estimated input values in the calculations.

An initial program cost estimate is based on the $75 voucher payment Austin chose to pay to citizens.

A program length must be estimated. Because a backyard chicken is expected to live approximately 10 years, 10 years was used as the estimated program life.

An interest rate must be estimated. Backyard chickens are working in municipalities and the average municipal bond rate in 2018 was 3.4%. The rate of 3.4% was used as the estimated discount rate in the initial analyses.

A cost of $163 per ton was used as the estimated cost savings and an annual savings of $27.04 per coop was used in the analyses. The estimated values were varied in the sensitivity analysis.

Value versus payback period

The payback period is the amount of time required for the undiscounted cash inflows to equal the initial cash outflow. Based on the estimated values, the payback period is 2.80 years. That is, a municipality that pays citizens $75 to purchase a chicken coop can expect to recover that cost in 2.8 years.

Given an annual savings of $27.04 per coop, the highest initial cost that would still achieve a payback period of at least five years is approximately $135, almost twice the rate paid to the citizens of Austin. Alternatively, keeping the program cost constant at $75 the minimum annual cost savings necessary to achieve a payback period of five years is $15.

A flock of four backyard chickens could eat about half of what they ate in this study and have a payback period of five years.

Net present value

The NPV is the sum of all the cash flows at a discounted rate based on the estimated discount rate and length of time until the cash flow is received.

Based on the estimated values, the NPV is approximately $150.90. That is, a municipality that pays citizens $75 to purchase a chicken coop can expect to gain $150.90 in present value dollars valued as of the day they start the program. Any program with an NPV greater than or equal to $0 provides value to the municipality and its citizens.

Sensitivity analysis was performed for the estimated inputs for the initial cost, the annual savings, the discount rate, and the length of the program. In the best case scenario, a municipality could pay a participant as much as $225 per coop and break even on the program. Even if the municipality paid only $75 per coop, the minimum annual cost savings could be as low as $9.00 to break even on the program. The shortest length of time for the program that would yield a benefit is three years, well below the average lifespan of a backyard chicken.

A flock of four backyard chickens could eat approximately one-third of what they ate in this study or live only three years and still make a worthwhile contribution to their communities.

Internal rate of return

The IRR is often described as the interest rate earned on a program. Based on the initial estimates, the IRR is approximately 34.1%. That is, a municipality that pays citizens $75 to purchase a chicken coop can expect to earn a return of 34.1%, well above the average rate paid by municipalities to borrow money and an excellent return on an investment in backyard chickens.

Profitability index

The PI is the ratio of the present value of the program cash flows to the initial investment. Based on the initial assumptions, the PI is approximately 3.0. That is, a municipality that pays citizens $75 to purchase a chicken coop can expect to earn receive three times the positive cash flow, in present value dollars, over the life of the program as the initial cost of the program.

Even if the municipality increases the payment to $225, it will break even on the program.

The bottom line value of chickens

By all four financial analysis methods, backyard chickens are valuable community members to reduce the costs of managing MSW. Under the initial assumptions, the payback period is short, the NPV is positive, the IRR is higher than the average cost of municipal debt, and the PI exceeds one. The sensitivity analysis revealed that an even higher initial cost (as high as $225), lower annual savings (as low as $2.25 per backyard chicken, or $9.00 per flock), higher interest rates (as high as 34.1%) or shorter program length (as short as 3.0 years) still resulted in a positive contribution from the backyard chickens to reduce food waste in their communities.

All financial analyses indicate that backyard chickens are a great MSW cost management program.

Backyard chicken owners should not overlook their chickens’ health as they are called into service as food recyclers. Feeding household food scraps to the chickens can change the composition of their diet as they will be enjoying an assortment of foods similar to what their keepers are eating. More research related to the composition of the diets being fed to food-recycling backyard chickens and their health is needed.

These feathered good citizens deserve a healthy diet as they work hard to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and save taxpayer dollars.

Chickens today serve by preventing household food scraps from increasing MSW management costs and entering landfills to create greenhouse gas. Whether their food-recycling or egg-laying comes first, there is no doubt about their value as contributing members of a healthy community.

Chicken Whisperer is part of the Catalyst Communications Network publication family.